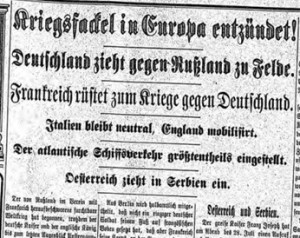

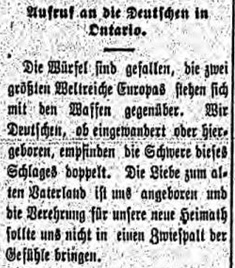

When the outbreak of the war became public in Canada, volunteers to support Great Britain were searched for immediately. The Parliament held a special session to discuss what to do about the war and to prepare the Canadian military.

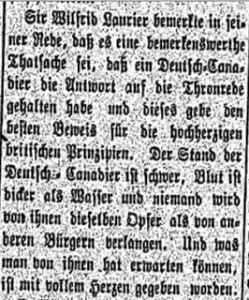

On August 12, 1914 it was reported that the Canadian government had asked for 21,000 volunteers to send to Great Britain, but that more than 60,000 men had rushed to enlist. Therefore, there would be a medical examination included at the enlistment facilities in order to find the healthiest and strongest men. Also, recruits would be divided into three groups: 1) single men; 2) married men; and 3) fathers with children. New recruits would be chosen from those who enlisted in that order.

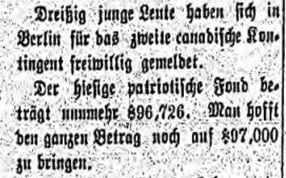

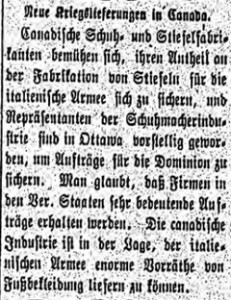

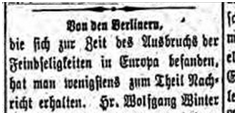

The paper also reported that Canada had bought two submarines, which they would provide to the British navy. Canadian soldiers would leave for training in about two weeks, at which point they would meet at Quebec and then travel to England. The first Canadian troops landing in Great Britain were announced in the issue of October 14, 1914. The British government was pleased with the troops, but asked Canada to send more money to purchase military equipment as well. By October 21, thirty young people from Berlin had volunteered for the second Canadian contingent, and Berlin had raised $896,726 for the Patriotic Fund.

(“Die kanadische Regierung…”, Berliner Journal, 5 August 1914; „Kurze Lokalnotizen“, Berliner Journal, 21 October 1914; „Die Freiwilligen für das dritte Kontingent…“, Berliner Journal, 3 February 1915)