Pre-1914

“The longer you look back, the farther you can look forward” – Sir Winston Churchill

It is a well-accepted fact that many communities were changed, and even shaped, by the impact of the First World War. From coast to coast, the war claimed the lives of thousands of Canadians, tested the industrial capacity of Canada’s cities, and strained federal and municipal politics. The Waterloo Region was no exception to the sweeping effect of the war upon their unique society. The Canadian Censuses, in 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, and 1911, reveal several trends that indicate that the Waterloo Region had a unique cultural and economic landscape in Southern Ontario. This first section discussed who the people of the Waterloo Region were ethnically, religiously, economically, and politically before the outbreak of the war. In order to understand the events and reactions of those living in the Region during the First World War, it is useful to develop an understanding of the people residing in the Region prior to 1914.

The Mennonites who first came to the Waterloo Region were known as the “Pennsylvania Germans,” who had settled in the northern region of the British Thirteen Colonies (New England) as early as 1753. They arrived under a British incentive to bring hard working “foreign Protestants” to North America, to counterbalance the French Catholic presence. The Mennonites were also known as individuals who could successfully develop agricultural settlements in any conditions. Due to their strong religious, ethnic, and familial ties, the Mennonites were not assimilated into New England society. The Mennonites, who religiously opposed violence, did not become involved in the American Revolution (1775-1783) militarily, and were not assimilated into the growing “American” nation.

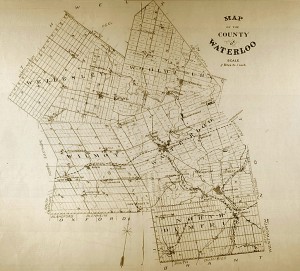

Between 1780 and 1830, the Mennonites emigrated from the United States into modern day Southern Ontario, primarily the region that was named “Waterloo” (to commemorate British and Allied victory at the famous Napoleonic battle), after 1815. Before the Region was named, , Pennsylvania Germans purchased 60,000 acres of land along the Grand Riverin 1805. This became known as the “German Company Tract”. The Mennonite settlers established a strong agricultural tradition, and established a German-speaking society. The pioneering, farming, and cultural roots that the Mennonites established in the Region attracted immigrants from the German States. Immigrants from the smaller kingdoms and duchies, which later formed a unified Germany, immigrated to the Waterloo Region. European Germans soon eclipsed the Mennonite population by 1830. Both the Mennonite and European Germans contributed to the German cultural identity of Waterloo Region.

(McLaughlin, Kenneth. The Germans in Canada. Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association, 1985.)

This sub-district of the Waterloo Region, made up primarily of the town of Waterloo, the city of Berlin (now Kitchener, as of 1917), Elmira, and surrounding rural communities, is best known for its Mennonite population, who arrived shortly after the turn of the 19th century. Mennonites and European Germans purchased land along the Grand River as a part of the German Company Tract to settle Waterloo North. The Mennonite community has inspired several tourist attractions, such as the St. Jacobs Market and the Pioneer Memorial Tower. Both of these landmarks are symbols of settlement, hard work, and unique Mennonite heritage. However, by 1911, Mennonite people were a minority in the Waterloo Region and lived collectively primarily in the rural areas of Waterloo North. The region’s German-Canadian population was comprised mostly of European German immigrants who outnumbered the Mennonites soon after their arrival in Southern Ontario. After the Mennonites settled the region in the early 19th century, waves of German immigrants seeking to escape the conditions of war torn Europe settled the region between 1812 and 1815. Until the 1860s, immigrants from Germany flooded to the region, often departing from Bremmen, Germany. Once they arrived in Quebec they travelled to the Waterloo Region, drawn to the region due to the overwhelming presence of German culture there.

(August 1914; Briethaupt, Catherine Olive. 1914 Diary (Briethaupt Diary Collection, Rare Books Room, Dana Porter Library, University of Waterloo), 3 August 1914; McLaughin, Ken, and John English. Kitchener: An Illustrated History. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1983.; McLaughin, Ken. The Germans in Canada. Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association,1985; Celebration of Cityhood 1912. Berlin: The German Printing and Publishing Co of Berlin, 1912; Fifth Census of Canada 1911, Volume I. C.H.Parmelee: Ottawa, 1912; Fourth Census of Canada 1901, Volume I. Ottawa: S.E.Dawson, 1902; Third Census of Canada, 1890-91. S.E.Dawson, 1893; Second Census of Canada, 1880-81. Maclean, Roger & Co: Ottawa, 1883; First Census of Canada, 1870-71. Ottawa: I.B. Taylor, 1873.)

While Waterloo North was largely shaped by an ethnically German population, Waterloo South, comprised of the small towns of Hespeler, Preston, and Ayr, as well as the larger town of Galt (present day Cambridge), present a different story. The small towns of Hespeler and Preston share a similar story to that of Waterloo North, comprised primarily of German Lutherans. Galt and Ayr are unique, as they reflect Anglo-Celtic ethnic and religious dominance.

In 1816, the Honourable William Dickson, a Scottish politician from Dumfries, Scotland, sealed the fate of the district. Dickson established the settlement of Shade’s Mills, and portioned out his 90,000 acres of land primarily to lowland Scots. Soon after, Dickson renamed the settlement Galt, named after Scottish novelist John Galt. Dickson advertised immigration to Galt, Ontario in Scottish newspapers and primarily attracted Scots from the lowlands of Roxboroughshire and Selkirkshire. Dickson’s efforts solidified British dominance in Waterloo South by 1911.

(City of Cambridge. “The Evolution of Galt.” Accessed April 15, 2014.)

The strong German presence in the Waterloo Region did not overshadow British imperialism in the late nineteenth century. On May 24, 1857, the Village of Berlin, alongside the newly inaugurated Village of Waterloo, celebrated Queen Victoria’s birthday with cannon fire and brass bands. Some citizens even boarded trains to Toronto to join in the imperial festivities there. The Queen’s birthday celebration in 1857 is one example of the ethnic German population rallying together to prove their loyalty to the British Empire. Beginning in 1899, the region enthusiastically celebrated the first Empire Day, which occurred on 24 May (Queen Victoria’s birthday).This event became an annual opportunity to celebrate ties to Great Britain.

(McLaughlin, Kenneth. Waterloo: An Illustrated History. Waterloo: Windsor Publications Canada, 1983.)

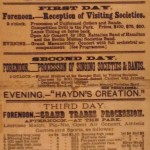

The Sängerfest, or “Singer Festival,” was an expression of German musical culture through a competition between Sängerbunds (German choirs). This public festival, also known as Liederfest, or “Song Festival,” drew competing choirs from all over the German communities of Southern Ontario and the United States of America. The first Sängerfest was held in Berlin, Ontario in August 1862. The Sängerfest allowed the German citizens of Waterloo Region to express their cultural identity and heritage in a nonpolitical and artistic manner. On 19 August 1875, the New York Times published an account of the Sängerfest in Berlin. It remarked that the first day of the ceremony was marked by a grand public reception, followed by an evening concert in a decorated hall, holding a reported 10,000 spectators from both Canada and the United States; the final day was marked by a grand ball. The Sängerfest not only attracted citizens of German ancestry, but also led thousands of tourists of mixed ancestry to attend the cultural event.

In 1893, the Concordia Choir in Berlin, the Male Choir in Elmira, and the Liederkranz Choir in Toronto, formed a Canadian Choir Federation, which became responsible for working with other German choir federations in planning the Sängerfests in Southern Ontario, notably in Berlin, Waterloo, Elmira, Guelph, Hamilton, and Toronto. Sängerfests were also held in the United States, such as the one held in Olympic Park in Newark, New Jersey, which drew in a crowd of 25,000 people. In August 1902, the first International Sängerfest was held in Waterloo, attracting choirs from all over Canada and the United States. The choirs performed primarily in German, but also in English. In 1912, the 50th Anniversary of Song Festivals in Canada was held. The Sängerfests in Waterloo-Berlin continued annually until the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914, when expressions of German culture and heritage stopped.

(Breithaupt, W.H. ‘The Saengerfest of 1875,’ 22nd Annual Report of the Waterloo Historical Society, Kitchener: 1935; Hayes, Geoffrey. “From Berlin to the Trek of the Conestoga: A Revisionist Approach to Waterloo County’s German Identity.” Ontario History 2, 1999: 131-150.; Leibbrandt, D. Gottlieb. ‘One hundred years of Concordia,’ Waterloo County Historical Society 61, 1973; “The German Saengerfest in Canada,” The New York Times, 1875; “Saengerfest Concert Draws Crowd of 25,000,” The New York Times, 1906.)

Waterloo North and Waterloo South are the pre-1955 federal constituencies, with key voting centers in Berlin and Galt, respectively. Between 1867 and 1914, in both constituencies, voting trends vary between periods of Conservative and Liberal dominance. This makes it difficult to state that either riding was staunchly Conservative or Liberal, as this trend of variation is indicative of voting habits leaning toward support for local elites. In some elections, national sentiments were reflected in the voting habits of the Waterloo Region, such as voting Conservative in 1878, due to the return of John A. Macdonald, and in 1911 due to issues with free trade. Otherwise, voting in the federal constituencies in the Waterloo Region is typical of politics elsewhere as voters voted for the individual who they believed best protect their interests.

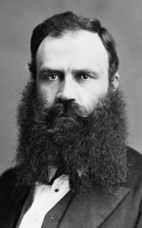

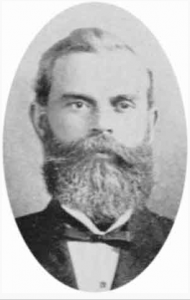

Isaac Erb Bowman (originally Baumann) was born in St. Jacobs on 17 August, 1832, and served as the first Member of Parliament for the constituency of Waterloo North, and belonged to the Liberal Party. Before becoming a Member of Parliament, he worked as a school teacher, in a tannery (which he later came to own), and was also a clerk, a treasurer and a postmaster for the village of St. Jacobs, and also represented the district in the pre-Confederation Canadian Parliament. He also acted as the president of the Ontario Mutual Life Insurance Company from its foundation in 1871. He held the position of Member of Parliament for Waterloo North from Confederation in 1867, until the 1878 election, when he lost to German-born Hugo Kranz. He was then re-elected in 1887, and defeated Kranz’s Conservatives again in the 1891 election. During his lifetime, Bowman represented the people of Waterloo North for over 20 years before dying in 1897.

Liberal Isaac Erb Bowman (originally Baumann) was born in St. Jacobs on 17 August 1832. Bowman served as the first Member of Parliament for the constituency of Waterloo North and belonged to the Liberal Party. Before becoming a Member of Parliament, he worked as a schoolteacher, in a tannery (which he later came to own), and was also a clerk, a treasurer and a postmaster for the village of St. Jacobs. He also represented the district in the pre-Confederation Canadian Parliament. Bowman also acted as the president of the Ontario Mutual Life Insurance Company from its foundation in 1871. He held the position of Member of Parliament for Waterloo North from Confederation in 1867 until 1878 when he lost to German-born Hugo Kranz. He was then re-elected in 1887, and defeated Kranz’s Conservatives again in the 1891 election. During his lifetime, Bowman represented the people of Waterloo North for over 20 years before dying in 1897. Bowman is an example of a prominent figure who was able to serve the region in parliament because of his well-established credibility with the region’s voters.

(Gemmill, J.A. ed. The Canadian parliamentary companion, 1887. Ottawa : J. Durie, 1887; Maclean Rose, G. ed. A Cyclopæedia of Canadian biography : being chiefly men of the time : a collection of persons distinguished in professional and political life : leaders in the commerce and industry of Canada, and successful pioneers. Toronto: Rose Pub. Co., 1886; PARLINFO, “Bowman, Joseph Erb.” Accessed April 20, 2014. http://www.parl.gc.ca/)

The end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 resulted in the unification of the German States into a United Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm I, the King of Prussia. On 2 May 1871, Citizens of Berlin, Ontario flooded the streets to celebrate the end of the European conflict in the form of a Friedensfest, or “Peace Festival.” They celebrated through parades, speeches, music, mass-choir singing, and fireworks. German clubs from throughout Canada and the United States, gathered alongside citizens of Berlin, and planted an oak tree to symbolize the end of the conflict.

In 1896, citizens gathered again to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Friedensfest. A year later, on 13 May 1897, a publicly funded monument was erected in Victoria Park in Berlin of Kaiser Wilhelm I, which was unveiled in a grand ceremony. The Friedensfest is an example of how the European German presence had vastly eclipsed that of the German Mennonite in Waterloo Region by 1871. This festival is also indicative of a growing “global village,” as citizens celebrated the end of a foreign conflict at home. Like the Säengerfest, the celebration of Friedensfest ended with the outbreak of the First World War.

(Friedensfest Denkmal Plaque, Kitchener, Ontario; Hayes, Geoffrey. “From Berlin to the Trek of the Conestoga: A Revisionist Approach to Waterloo County’s German Identity.” Ontario History 2, 1999: 131-150.)

Hugo Kranz was born in Lehrbach, Germany on 13 June 1834. He immigrated to the United States with his father in 1851 before moving to Canada and settling in Berlin, Ontario in 1855. In Berlin, his father opened a general store, which Kranz continued to run after his father’s death in 1875. Soon after arriving in Berlin, Kranz began a long political career, serving first as a town clerk from 1859 until 1867. He then served as the reeve of the village of Berlin between 1869 and 1870, before being elected mayor of the town of Berlin in 1874. Kranz served as mayor until 1878, and in that time, also helped found the Economical Mutual Fire Insurance Company. In 1878, Kranz was elected as a Conservative Member of Parliament for the constituency of Waterloo North. This was during the same election that John A. Macdonald was re-elected Prime Minister of Canada. Kranz was re-elected in the 1882 election, but lost his position in the 1887 election, and was defeated again in 1891. Kranz is significant as he was an immigrant of German origin who, like many other Germans, led a very successful life.

(Celebration of Cityhood 1912. Berlin: The German Printing and Publishing Co of Berlin, 1912.; PARLINFO. “Kranz, Hugo Carl.” Accessed April 20, 2014. http://www.parl.gc.ca/)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.