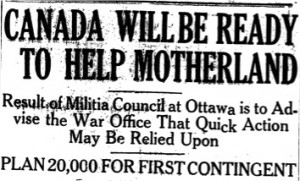

On 30 July, the Canadian Militia Council advised the War Office that, if Great Britain entered the war, Canada would be expected to spring into action quickly. This advice resulted in a special meeting of the Militia Council, on 31 July. The council discussed Canada’s mobilization and the raising of a contingent of 20,000 to 25,000 men, to aid the Imperial Forces in the event of war.

This meeting, and the decision that Canada would raise a contingent, if Great Britain were pulled into the war, was made independent of any request from the British War Council. Although no formal request had yet been made, the Canadian Government wanted Great Britain to know that Canada could be relied on for assistance if needed. At this point Canada’s Regular Forces, the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR), were ordered to be ready for mobilization.

(“Canada Will Be Ready to Help Motherland,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 31 July 1914.)