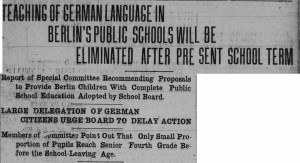

Berlin’s Public School Board voted 5 to 3 to remove the study of German from the public school curriculum beginning the following September. Many spoke in opposition to the movement, including Berlin Mayor J.E. Hett who insisted that bilingualism would be an advantage to the 1400 Berlin students currently learning the language. Prominent business man and president of the German School Association, L.J. Breithaupt stated both in public and in his diary that there was strong support in the community to keep German language classes in the schools. He stated that the fact that over two thirds of pupils studied German in school was proof of its popularity.

Those who defended the removal of German said that the war was not a factor in their decision. They claimed that German was removed in order to accelerate the teaching of more essential or practical subjects, especially since many students left school before completing the highest grade. (The Berliner Journal also reported this story.)

(“Teaching of German Language in Berlin’s Public Schools Will Be Eliminated after Present School Term,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 18 March 1915.; Breithaupt Diary Collection, Rare Books Room at Dana Porter Library, University of Waterloo)