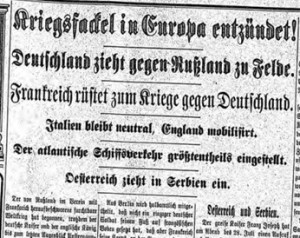

When Great Britain declared war, the long-standing alliances between the European Powers had come to a head. The Triple Alliance was formed in 1883 between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, against Russia and France. Great Britain had never been formally part of this alliance, but had been closely linked to it due to her apprehension of French and Russian aggressiveness as well. This, however, changed when Great Britain became wary of Germany’s naval growth after 1902.

As a result Great Britain became aligned with France in 1904 and Russia in 1907 forming the Triple Entente. The Triple Entente sought a balance of power in Europe, a strengthening of the treaty laws to help maintain peace and the status quo, and disarmament across Europe. They also made a commitment to one another to raise a land force and naval force that exceeded the strength of the Triple Alliance’s forces. This commitment was of extreme importance now that all six nations were at war.

(“Triple Entente and the Alliance,” Berlin Daily-Telegraph, 6 August 1914; Visual: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/worldwarone/images/article/alliance_entente.gif)