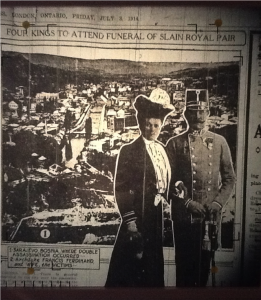

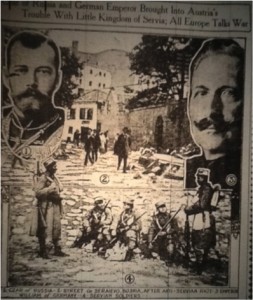

On Sunday 28 June, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The couple was in Sarajevo for their annual trip to the annexed provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

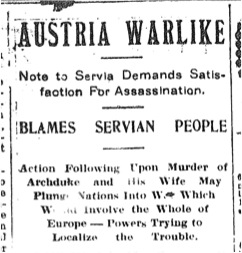

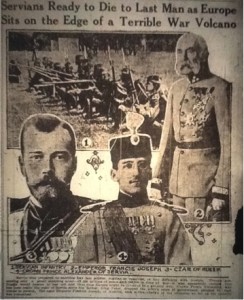

Two assassination attempts were made. After surviving a bomb attempt, the couple was shot by Gavro Prinzip, an 18-year-old Bosnian-Serb student, as they travelled by car. The couple died later that day. Immediately, there was international concern that the assassination would further strain the relationship between Austria and Servia. Newspapers in the Waterloo Region, including the Berlin Daily Telegraph, the Ayr News and the Elmira Signet, covered this story. The region, along with other communities around the world waited to see what would result from this assassination.

(“Assassinated by Student,” Ayr News, 2 July 1914; “Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and his Wife Assassinated by Student” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 29 June 1914; “Heir to Austria Throne and Wife Assassinated,” Elmira Signet, 2 July 1914; Photo Origin: London Free Press, 3 July 1914.)