The first time the Cunard vessel Royal Mail Ship Lusitania, a British passenger ship, made the news in 1915 was on February 11. The sh ip had crossed the Atlantic flying an American flag rather than the Union Jack. The Captain made the decision to protect his neutral passengers after receiving word that German submarines were active near Ireland. According to the British Foreign Office, this act was not sanctioned by the British government. After this incident the Lusitania flew the Union Jack.

ip had crossed the Atlantic flying an American flag rather than the Union Jack. The Captain made the decision to protect his neutral passengers after receiving word that German submarines were active near Ireland. According to the British Foreign Office, this act was not sanctioned by the British government. After this incident the Lusitania flew the Union Jack.

Sadly, the ship made headlines again when it was torpedoed by the Germans on May 7, 1915 off the coast of Ireland. The sinking dominated newspapers during May and into June 1915. At first, it was reported that the ship took about twelve hours to sink and crew and passengers had been rescued. The RMS Mauretania, owned by the same company, was set to sail on May 29 but its voyage was quickly cancelled.

The sinking turned out to be a larger disaster than originally expected as by May 13, it was known the Lusitania was fired upon with no warning, sunk within thirty-five minutes, and over thirteen hundred people had lost their lives.

Interestingly, during this period, travelers had been warned via newspapers that a war was being fought and any ship in the Atlantic Ocean under a British flag was liable to be fired upon and sunk; therefore passengers were traveling at their own risk. But there was also reason to believe the ship would not be in any danger: the Lusitania carried many neutral American citizens, and no soldiers, masked guns, gunners, or special ammunition were being transported other than a few cases of cartridges. (Germany justified the sinking by claiming the ship carried military personnel and.) Finally, the ship held the transatlantic Blue Riband award for speed, leading some to believe that even if the ship was fired upon, it could outrun the torpedoes. As Maritime Law states that in times of war, merchant ships are to be given a warning before being fired upon, it might have theoretically been able to outrun the torpedoes. The Lusitania was given no such warning.

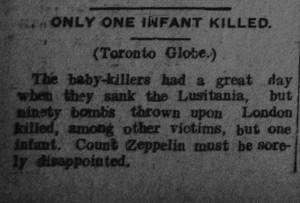

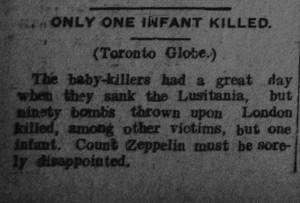

This devastation would be reported on throughout May and into June, and was used to demonize the Germans. A good example of this was seen on June 2, 1915, when the Berlin Daily Telegraph reprinted a story from the Toronto Globe about how the “baby killers” must have been disappointed that their recent zeppelin bombings in London had only killed one infant. It was also learned by June 4, that the Lusitania had been carrying eighty-two bags of mail, all now lost at sea. At the Roma, a local theatre, the planned program for June 3, included showing pictures of the Lusitania up to her sinking.

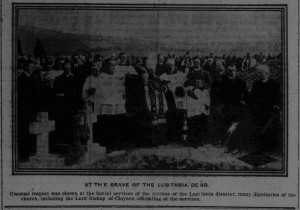

“At the Grave of the Lusitania Dead,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, June 2, 1915.

“At the Roma,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, June 3, 1915.

Bruno S. Frey, et al,., “Interactions of Natural Survival Instincts and Internalized Social Norms Exploring the Titanic and Lusitania Disasters,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 107, no. 11 (2010): 4862-4865.

“Hoisted American Flag,” Ayr News, February 11, 1915.

Image of the Lusitania, Ayr News, May 13, 1915.

“Only One Infant killed,: Berlin Daily Telegraph, June 2, 1915.

“Sailing of the Mauretania is cancelled,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, May 11, 1915.

“The “Lusitania” Mails,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, June 4, 1915.