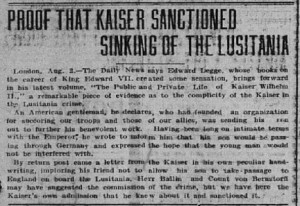

By August of 1915, Canadians were becoming more and more interested in the possibility of the USA entering the war on the side of the Entente. The war was becoming largely a contest of manpower, and the added contributions of a massive country like the US would inevitably tip the balance in the favour of whichever side it joined. The sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine, therefore, was still often discussed as a possible cause for war, even three months after the event. This short article from August 3, 1915 in the Berlin Daily Telegraph claims the existence of a letter written by the Kaiser himself “proves” he had personally approved of the attack on the Lusitania before it occurred.

Stories like this one appeared often in the local papers, which continuously tried to judge whether US intervention might happen and when. By the end of August, after the sinking of the HMS Arabic – which again held American passengers – reports about the US officially denouncing Germany further intensified.

Berlin Daily Telegraph, July 22, July 24, August 3, August 20, August 24, 1915.