The Berliner Journal was a German newspaper published in Berlin, Ontario between 1859 and 1918. As there was at that time, and still is, a large community of German speaking immigrants in the Waterloo region, investigating the German perspective is an essential step towards gaining a full understanding of the regional perception of the War. 70% of the population of Kitchener in 1911 was of German origin. Therefore, the German culture and heritage played a vital role in the overall social, political and economic structure of the region. The role of the German newspapers was to preserve the region’s cultural heritage and language as well as to help immigrants adapt to their new lives in Canada.

The Berliner Journal was the biggest German newspaper in the Waterloo region and was founded by the German immigrants Friedrich Rittinger and John Motz in 1859.

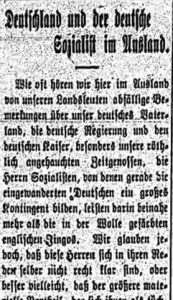

The outbreak of the First World War posed as a serious challenge for the Berliner Journal due to the growing anti-German sentiments it inspired. Rittinger and Motz approached the situation as mediators. By encouraging the German-Canadians to stay neutral and by including various perspectives in their reports, they hoped to protect the German community from unnecessary persecution. Nevertheless, the paper’s circulation decreased during the war due to the difficult circumstances. In October 1918, the federal government finally banned all German newspapers in Canada, and as a result, the editors of the Berliner Journal decided to end production.

(Löchte, Anne. Das Berliner Journal 1859-1918. Eine deutschsprachige Zeitung in Kanada. Göttingen: V&R unipress 2007. Print. pp. 167-200; English, John and Kenneth McLaughlin. Kitchener: An Illustrated History. Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press 1996. Print. p. 233)