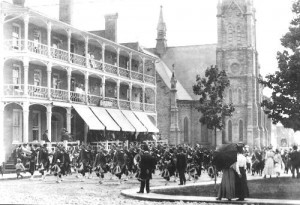

The Sängerfest, or “Singer Festival,” was an expression of German musical culture through a competition between Sängerbunds (German choirs). This public festival, also known as Liederfest, or “Song Festival,” drew competing choirs from all over the German communities of Southern Ontario and the United States of America. The first Sängerfest was held in Berlin, Ontario in August 1862. The Sängerfest allowed the German citizens of Waterloo Region to express their cultural identity and heritage in a nonpolitical and artistic manner. On 19 August 1875, the New York Times published an account of the Sängerfest in Berlin. It remarked that the first day of the ceremony was marked by a grand public reception, followed by an evening concert in a decorated hall, holding a reported 10,000 spectators from both Canada and the United States; the final day was marked by a grand ball. The Sängerfest not only attracted citizens of German ancestry, but also led thousands of tourists of mixed ancestry to attend the cultural event.

In 1893, the Concordia Choir in Berlin, the Male Choir in Elmira, and the Liederkranz Choir in Toronto, formed a Canadian Choir Federation, which became responsible for working with other German choir federations in planning the Sängerfests in Southern Ontario, notably in Berlin, Waterloo, Elmira, Guelph, Hamilton, and Toronto. Sängerfests were also held in the United States, such as the one held in Olympic Park in Newark, New Jersey, which drew in a crowd of 25,000 people. In August 1902, the first International Sängerfest was held in Waterloo, attracting choirs from all over Canada and the United States. The choirs performed primarily in German, but also in English. In 1912, the 50th Anniversary of Song Festivals in Canada was held. The Sängerfests in Waterloo-Berlin continued annually until the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914, when expressions of German culture and heritage stopped.

(Breithaupt, W.H. ‘The Saengerfest of 1875,’ 22nd Annual Report of the Waterloo Historical Society, Kitchener: 1935; Hayes, Geoffrey. “From Berlin to the Trek of the Conestoga: A Revisionist Approach to Waterloo County’s German Identity.” Ontario History 2, 1999: 131-150.; Leibbrandt, D. Gottlieb. ‘One hundred years of Concordia,’ Waterloo County Historical Society 61, 1973; “The German Saengerfest in Canada,” The New York Times, 1875; “Saengerfest Concert Draws Crowd of 25,000,” The New York Times, 1906.)