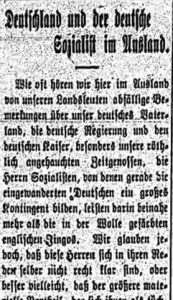

In the years leading up to the war, Canadian immigration was at an all-time high. Many of these immigrants came directly from Germany and arrived with different political and nationalistic ideals. This article was written by a German immigrant and addressed other recent German immigrants who held socialist views and were opponents of the German emperor. The writer admitted that socialist ideas could be useful, but argued that it did not mean that one cannot love his homeland and worship Kaiser Wilhelm. He claimed that Germany was the best ruled country in the world under the emperor’s constitutional monarchy. The author dismissed the complaint of the socialists that Germany was wasting money on a massive army and navy. Peace in the world was a nice ideal, the article continued, but was not possible at this time. The writer claimed that Kaiser Wilhelm had led Germany to its leading position in the civilized world and that the disarmament of the German army would lead to unemployment.

This strong defence of German militarism is interesting coming just after the declaration of war. In the future, the Berliner Journal would be forced to choose the words it spoke about Germany and the Kaiser much more carefully.

(„Deutschland und der deutsche Sozialist im Ausland“, Berliner Journal, 5 August 1914)