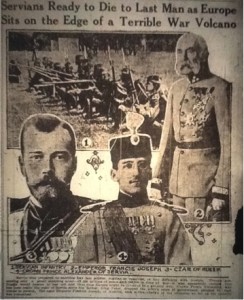

In the summer of 1914, London, Ontario hosted the annual Cadet camp, at Carling Heights, for the competition of South-western Ontario Cadet Corps. This was the largest Cadet camp to date since their founding in 1879. Over 1400 cadets participated in this camp. Cadet Corps from Waterloo Region attended this camp and competed in a number of competitions.

In the shooting competitions for the Beck Trophy (named in honour of Sir Adam Beck, Minister without Portfolio in Parliament from 1905 to 1914), the Waterloo Cadets placed second, only four points behind the winners from London. Chatham, Galt and Essex took the subsequent places. The Waterloo Region, therefore, had two of their Cadet corps place in the top four positions, a testament to their skill. The Waterloo and Galt corps continued to place in the top ranks in the other competitions. The oldest cadets at the camp were described as having the assuredness and steadiness of regulars. Unbeknown to them, this type of training would help prepare young Canadians for an upcoming war.

(“Cadet Camp at London,” Waterloo Chronicle- Telegraph, 23 July 1914; “Photo Origin: London Advertiser, 11 July 1914.”)