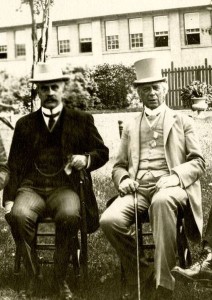

Almost immediately after Canada entered the war, the issue of German officers and reservists in Canada arose. As early as 7 August, the Canadian Militia Department and the Dominion Cabinet took steps to ensure that German officers and reservists were prevented from returning to Germany. German reservists were encouraged the report to authorities to state their intentions; a failure to do so would likely lead to arrest and confinement. Despite this hostility, reservists in the Waterloo region were assured that if they wanted to remain in Canada and proceed with their normal daily life, under parole, they would not be harassed. Any German reservist in Berlin and Waterloo was to report to Captain Osborne, Captain of the “C” Squadron of the 24th Grey’s Horse Regiment, stationed in Waterloo Region.

(“Will arrest German Reservists if they seek to leave Canada,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 8 August 1914; “Will arrest German Reservists if they seek to leave Canada,” Waterloo Chronicle-Telegraph, 13 August 1914; “German Reservists in Dominion must state intention at once,” Waterloo Chronicle-Telegraph, 13 August 1914; “Reservists Handed in Their Parole,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 8 August 1914; “Reservists Handed in Their Parole,” Waterloo Chronicle Telegraph, 13 August 1914; “War News,” Elmira Signet, 13 August).