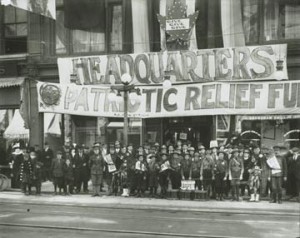

On 11 August, a suggestion was made in various localities across Canada, to establish a Patriotic Fund much like the one that had been established during the South African War. During the South African war, approximately $500,000 was raised to provide relief to the families of men who were at the front and men who had taken sick or been wounded during their service. Almost $150,000 of this money was never paid out, and it was suggested that this sum form the beginning of the new Patriotic Fund. Individuals, companies, and communities would then be asked to raise more money for the fund.

In addition to considering another patriotic fund, Canadians also started raising a fund for a Canadian Hospital ship. On 11 August, the British Admiralty accepted the offer made by the women of Canada to provide a Hospital Ship for the British Army. In the Waterloo Region, the Princess of Wales Chapter of the Daughters of the Empire explained that it was the desire of the “women of Canada to equip a Hospital ship to be placed at the disposal of the Admiralty.” Anyone wishing to donate to the fund could do so at Roos’ and Swaisland’s Drug Stores in Berlin and at E.M. Devitt’s Drug Store in Waterloo. The press would publish any donation made at these locations.

(“Would Join Force,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 11 August 1914, “To Raise Funds for Canadian Hospital Ship,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 11 August 1914, “Hospital Ship is Accepted,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 11 August 1914, “Hospital Ship is Accepted,” Berlin Daily Telegraph, 12 August 1914)